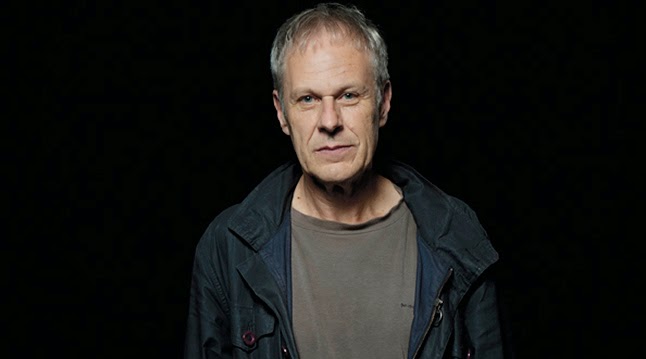

STEPHEN DIXON

by Christopher Sorrentino and Alexander Laurence

Stephen Dixon is the author of several books of fiction,

short stories, plays. His latest book is called INTERSTATE (Henry Holt). He

lives in Baltimore.

Sorrentino: (1) I've heard you mention that when you sit

down to write a short story, you'll enter into the process without any idea as

to where you're going--that is, you'll just sit down at the typewriter and

begin by writing whatever comes into your head.

If I haven't completely misrepresented what you meant, does the process

extend to novel-length projects?

INTERSTATE has a precise and defined formal structure, it is clearly not

extemporaneous. Was the structure

applied to it after the book was begun?

I'm particularly curious since the first section is so self-sufficient;

was it written first?

Stephen Dixon: That is how I write a short story about 95%

of the time. First draft in about an hour or if it’s a longer first draft, two

hours; then spending about a month or three on the final draft. The way I wrote

Interstate was like this: I wrote the first Interstate; it turned out complete

and self-sufficient by the nature of its story. Then I thought I’d continue the

novel from where I left off, but that turned out to be too traditional an approach

for me and the language was wooden if not dead. Then it came to me how to do

it: I wanted the subsequent Interstates to extrapolate on what I wrote in the

first Interstate, and to unearth the things between and in the lines; I wanted

an extension, tightening, focusing, reimagining of the events, a zeroing in on

certain choice events, and a chance to broaden the emotional content of the

first part by elaborating or changing. I also saw it as a new kind of road

novel, where the characters get closer to their destination in each Interstate

(chapter) till a final chapter, which is both ambiguous and a wrapping up, and

where they’ve arrived safely home.

Sorrentino: (2) Could you discuss the recurring concern in

your work with the idea of varied and conflicting results occurring from an

initial set of circumstances? What seems

to separate your work from the usual use of this RASHOMON-like technique is

that frequently the divergent stories are attributed to one narrator. INTERSTATE is like that, though it slips from

first to second to third person, and I'm also thinking of stories like

"Goodbye to Goodbye."

SD: It is Rashomon-like except, as you say, the narrator

stays the same. What's different is that my different persons telling the story

are first, second, and third persons; I also wanted to tell it in the major

tenses, far as I'm concerned: past, present, future, conditional. In other

words, I wanted the same or somewhat changed event told from every person and

perspective and tense device. A modern Rashomon, though I wasn't thinking of

Rashomon when I wrote it.

Sorrentino: (3) You

have published nearly twenty books in twenty years, yet your work is much less

well-known than that of many of your contemporaries, perhaps in part because

until recently you were published by such houses as Street Fiction Press, Johns

Hopkins, and British American Publishing.

Also, you've said that you decline to write reviews or essays of any

kind. Have you turned to small presses

and rejected "commercial" assignments because of the compromises

trade houses and such assignments demand that you make? You seem to have found a home with Henry Holt

for the time being, and INTERSTATE seems

to have been positioned as the book with which you might gain exposure to a

wider audience. Are you gratified that

your work is finally beginning to receive widespread attention?

SD: I could care less how my work is received. Long ago I

decided that worrying about getting published and getting reviewed and about

the qualities published and the places where one's reviewed and what page the

review is on, etc., was a waste of time and would take time away from what I

liked doing most in life and that's writing. I don't write for an audience or

to be published and certainly not to get attention or reviews or fellowships or

prizes. None of that means anything to me. I write because it's what I like to

do, and that Holt is doing my work now is fine if Holt does a good job of it,

which is printing it so normal eyes can read it and putting a cover on a book

that doesn't repulse me and mislead the reader. I haven't abandoned the

publishing world that nourished me for so long: small presses. Hijinx Press, a

small publisher in Davis, CA, will be publishing a book of mine in Spring 96

called MAN ON STAGE: Play Stories, four pieces of fiction written for the stage

or four one-act plays written for book form. I'm excited about that book as I

am about anything I've done. I don't write for money, have never cared for

money, realize the necessity of SOME money, but have never written a word or

directed a work of mine to any place for money. Worrying about dough is another

thing that'll stop the flow.

Laurence: (4) Why do

you think that you wrote a book dealing with such an intense emotional

situation?

SD: To me, the best fiction is about emotion. And I wanted

to write the most emotional book I could. There's no emotional occurrence

greater than the love of a parent for a child and the possible or actual loss

of that child, which is why I used that theme for my novel. Why not write about

intense situations? It's probably more challenging to a writer to make banal

events interesting, but it's never been rewarding to me. The mundane should

only be written in fiction as a reward for the emotional intensity that

preceded it.

Laurence: (5) Could

you tell us a little about your meticulous writing habits?

SD: I write whenever I can and I do all my other nonwriting

work to make room for my fiction writing. All the other work is an interference

to my writing but, contradictorily and ironically and painfully, that

nonwriting work is necessary to my writing because it gives me a little income

to have a family and lead a fairly normal life and have a modest home to write

in. I get all the nonwriting things out of the way before I write. That way

I've cleared time for myself to write. And then I just write, soon as I can in

the morning (I teach in the afternoons) and with as few distractions as I can

manage. I don't gripe about my nonwriting work because that would be futile.

And if I let the nonwriting work build up, I'd have to face it some day so best

to get it out of the way now. I write on a manual typewriter, nonelectronic and

certainly not a word processor. The WP gives writers the illusion there work is

better because it looks better on the monitor and printout. I write a first

draft quickly, let it just pour from my head, since I believe that my

imagination will furnish me material forever and furnish me ways to write that

material forever too. I rely on my imagination and it's never failed me. I've

never had a writer's block in 35 years of writing and I've probably written

every day in 35 years but about 50 of them (time off for getting from NYC to

Maine; sickness, funerals, hangovers, day I got married and my two-day

honeymoon, the rest...)

My first

drafts are written in hour to two-hour spurts, as I mentioned. The novel

chapters are usually written in similar spurts. First drafts of ten pages have

turned into 5-page stories and 200 page novels. Things take off sometimes, and

sometimes they really take off and I have to run behind with a whip trying to

stop them, and sometimes things need to be reduced, like a 10-page story to

five pages. I never know what I'm going to write about, unless it's a novel.

Then the ideas come in relation to what was written before it. And style

follows the story; I don't know what the style will be till it's there on the

page, though I hate repeating styles and repeating stories, unless the repeat

is a variation of what came before it. I write hard and I type fast and I redo

a page from twenty to forty times and sometimes sixty times till I'm satisfied

but completely satisfied with it. And yes, I drink a couple of cups of coffee

while I write. Coffee to me--this isn't a plug, you know--keeps my mind alert

and doesn't stuff me and make me tired and gives me something to do if I need a

break. But the writing ... I write page one of the first draft of page one

twenty to sixty times till I'm satisfied and then I go to page two of the first

draft, and that's how I write, slowly building up pages, sticking with the same

story or novel till I'm finished with it, and then starting a new novel or

story or playstory the following day. For I try to write every day.

Laurence: (6) What

sort of writers of the past do you think are important influences for you?

SD: Many important influences and the most important of them

I had to stop reading because they were being too influential. I never wanted

to sound like any other writer but I certainly wanted to be as good a writer as

the writers I liked to read. I never read drecht; I don't read genre fiction. I

read seriously and for an intense reading experience. Thus, there are very few

writers that come up to my standards of reading and very few very good writers

who have sustained the quality of their fiction in book after book or story

after story. But I don't see why a writer can't do that, always be good and

always grow from his or her earlier works. If a work is lousy, one shouldn't be

reluctant to abandon and destroy it. Each year I throw out works I wrote first

drafts of but which stunk, which is why I never went back to them. And I have

four apprentice novels, though at the time I didn't think they were apprentice

works, which I have given in their unpublished versions (manuscripts) to the

John Hopkins Library, which has my papers. I'll never go back to them and

anybody can look at them as works where I practiced how to write but not works

that I now want to see in print. The writers I've loved: Homer, Virgil, Dante,

Dostoevski, Tolstoy, Chekhov, Gogol, Babel, Hemingway, Bellow, Malamud, Richard

Wright, Kafka, Beckett, Joyce, Mann, Camus, Tanizaki, Sartre, T. S. Eliot,

Böll, Conrad, Doris Lessing, F. W. Dixon, James Robert Dixon, a story by Landolfi,

a play by this guy, a poem by that woman, some children's literature: Milne,

Carroll, and so on... The list is endless and I am always reading.

Laurence: (7) You

seem to have an amazing energy when it comes to writing fiction. Where do you

think this comes from? And what sort of fiction do you see yourself engaging

with in the future?

SD: No matter how many drafts of a page I write, I always

want it to have the spontaneity and freshness of the first draft. Some writers

take the juice out of a work by rewriting or overwriting it. I try to always

make those lines and characters and dialog and situations bounce around on the

page and keep bouncing. The energy in my writing might come about from my love

of the act of writing and rewriting. I don't think exciting or even interesting

work comes from a writer who doesn't like the act of writing. I write with this

premise in mine: that nobody asked me to write; I'm writing because I love to

write. What sort of writing in the future? I don't know, and I love not

knowing. I am always in a rush to work on and finish a new work so I can see

what'll come out of my head with the next work. But I never finish a work till

I am entirely satisfied with it. So as excited as I am when I write a piece

now, I look excitedly forward to what I'll write in the future. What I do now

lays the groundwork for what I do in the future. There's a certain irony in

wanting to advance to the next work while tying yourself down with your current

work till it is in your mind perfect, or till you can't do anything more with

it. Anyway, let's just say writing is an exciting process and maybe that's why

my writing comes out energetically.

Laurence: (8) A

certain amount of writers have lived like professors: dealing with a dead

culture in an often predictable way, a culture which only produced cultivated

entertainments. Do you think that since you have worked in an assortment of

jobs and have lived an unwriterly life, that has helped you keep your interest

and language alive?

SD: Having lots of jobs certainly gave me material to write

about. There's just about nothing to write about in academia which is why I've

written so little about it. The language around campus is usually stiff and

careful, while the characters I like to write about have language that's lively

and ungrammatical and careless. Now, I don't need the jobs for material,

though, since my writing for the last ten years has been so interior and

getting more interior all the time. That doesn't come about because I'm working

in rather dry academia; it's because I'm exploring themes and material and

subject matter in myself that I've never before approached, dug at and

unearthed.

Laurence: (9) How

do you see future of magazines and publishers? And good advice for today's

young writers?

SD: There'll always be lots of magazines but only a few

that'll publish fiction or just literature of quality. That's because there

aren't enough readers to support magazines that publish stuff like that, and

because serious literature doesn't service commercial magazines. As for

publishing: if I can be published, can't anyone? My books never made money yet

publishers have backed them, though sometimes it's taken forty publishers to

look at my work before one took it. I don't care who publishes me as long as

that publisher publishes me well. I know there's a lot of talk about how

publishers are part of conglomerates and good work is having more difficulty

finding a publisher, but maybe good writers haven't tried as hard as I have to

get the work published, or have been willing to just have a one-man operation

(Garbage, by Cane Hill Press), (FRIENDS, by Asylum Press), or a two-man

operation (WORK and NO RELIEF: Street Fiction Press) publish their work.

Good advice

for writers: Write very hard, keep the prose lively and original, never sell

out, never overexcuse yourself why you're not writing, never let a word of

yours be edited unless you think the editing is helping that work, never

despair about not being published, not being recognized, not getting that

grant, not getting reviewed or the attention you think you deserve. In fact,

never think you deserve anything. Be thankful you are able to write and enjoy

writing. What I also wouldn't do is show my unpublished work to my friends. Let

agents and editors see it--people who can get you published--and maybe your

best friend or spouse, if not letting them see it causes friction in your

relationship. To just write and not worry too much about the perfect phrase and

the right grammar unless the wrong grammar confuses the line, and to become the

characters, and to live through, on the page, the experiences you're writing

about. To involve yourself totally with your characters and situations and

never be afraid of writing about anything. To never resort to cheap tricks,

silly lines that you know are silly--pat endings, words, phrases, situations,

and to turn the TV off and keep it off except if it's showing something as good

as a good Ingmar Bergman movie. To keep reading, only the best works, carry a

book with you everywhere, even in your car in case you get caught in some

hours-long gridlock. To be totally honest about yourself in your writing and

never take the shortest, fastest, easiest way out. To give up writing when it's

given to you, or just rest when it dictates a need for resting; though to

continue writing is you're still excited by writing. To be as generous as your

time permits to young writers who have gone through the same thing as you (that

is, once you become as old as I am now). To not write because you want to be an

artist or to say you're a writer. And to be honest about the good stuff that

other writers, old and your contemporaries, do too. And not to think that any

stimulant stronger than a coupla cups of coffee will help your writing. Sleep

helps it, keeping in shape, but little else, along those lines. And not to

listen to God himself if he tells you that you aren't a writer and will never

be one, if you still think you are a writer or can become a good one, or if you

get a kick out of writing. There are a lot of writers my age out there who

can't stand young writers because they're young and full of potential and

because they have a clean slate and nowhere to go but up and who are still

exciting about the act of writing.

September 1995