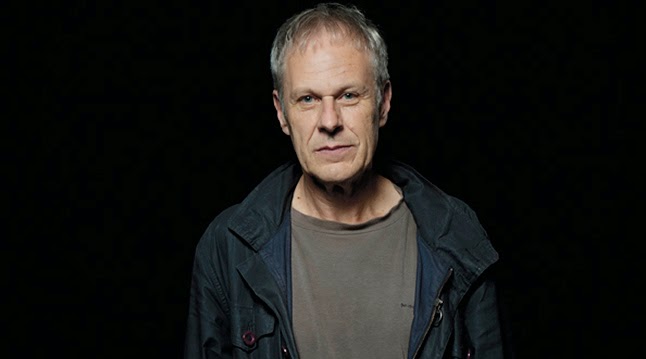

INTERVIEW

WITH DENNIS COOPER

by

Alexander Laurence

Serial

murders have become more prevalent in American Society. Are you very interested

in them?

Dennis

Cooper: To a degree. I don’t think that they’re interesting people, but I’m

interested in the books about serial murderers, and the material you can get

from their exploits. They’re not real smart people.

William

Levy wrote about your novel Frisk: “I was involved with a theurgical killing of

a boy; it wasn’t all that great: nothing worth doing again--no matter how pop

it has since become.” I think that Levy missed the point of the book entirely.

What do you think about this misreading?

DC:

Sure. It’s not a book about a murder. It’s about a guy who fantasizes about

killing people. It’s a totally different thing. This character has absolutely

no clue about how to kill people. He’s never done it. He just spends his life

dreaming about it. Presumably, it has no relationship to what it’s like to kill

a boy. He’s not John Wayne Gacy; he’s just a daydreamer. The point is: he’s no

different than the kid who daydreams about Tolkien. The book is not about a

serial murder.

How

was it living in Amsterdam?

DC:

On one hand, it's a great country. They're very humane. You get free health

care. On the other hand, there's nothing to do there. It's very cold. They

don't support art there. They're very conservative. They support artists born

in Holland, but they make bad art. Socialism is great for human stuff, but

Socialism sucks for art.

I

always have this feeling that I’m reading that happened about ten years ago

when I read your work. When did you write your novels and roughly what time

frame are they set in?

DC:

Frisk was written around the time I lived in Amsterdam. It was my revenge on

Holland for the unpleasant time I had there. Closer was set in high school.

Closer had a couple of adults in it, but it was more about being a teenager.

Frisk was also about being a teenager, and some experiences people have in

their early twenties, and some of those expatriate things. Frisk was definitely

about the distortions that arise in becoming an adult. I think of Closer being

set in the late 1980s, and Try, set in now, 1994. In the book, Hüsker Dü has

already broken up, and it’s before Sugar. Slayer is still around.

What

are some of your favorite bands now?

DC:

My favorite band is Sebadoh. They’re from Massachusetts. The bass player is

from Dinosaur jr. That is the first great band for me since My Bloody

Valentine. I like Pavement. I like that emotionally fucked up, slacker stuff.

You’re

into the body. Your books present the body as a bunch of tubes. The characters

act out their will on the body, trying to uncover the truth of the other.

Another person. Can you talk about that?

DC:

For all practical purposes, the body is a machine with all this stuff inside. I

guess the characters in all my books are like this, though not so much in the

new one, Try. Since they don’t believe in religious stuff. You just see what’s

in front of you. And what’s in front of you is this body, right? It has all

this appeal to you, and you desire it, or you are fascinated by the body. In

many ways, you are just like a kid, and kids try to take things like toys apart

to see how they work. These are people who figure “Well, if I open up this body

and look what’s inside it, I’ll know what makes me feel so overwhelmed, or so

out of control when I’m with this person.” It just that: trying to deal with

people in a practical way. Even if you think that there’s spirituality, or

something; you can’t take apart the mind and figure what it’s like. These are

people who objectify other people into being like that, as a way to try to

figure things out, and they willfully ignore emotion and spirituality and all

that stuff. The body interests me in that way, and it interests me that the

text is like a body. I like the writing to be eviscerated too, opened up in

different ways.

How

much thought do you give towards spirituality? And what do you think of the

idea of sympathy in your new work?

DC:

Spirituality? Not much. But I have a lot of sympathy towards everybody in the

books. One of the things people don’t like about it is that I don’t have a

moral stance in the books. The books are all really sympathetic. People can

have their own moral outlook. The books don’t have to reinforce it. That’s what

I think. Make up your own mind. Try has a little more sympathy obviously for the

kids, but I think all those characters are sympathetic. It’s just that I’m not

sentimental about them. The books give them all a chance to speak, pick their

minds, do what they want to do. The world sucks. People are fine. It’s the

world that sucks.

Television

shows images of evil, to cause a robotic reaction in people, to make them say:

“Let’s do something” or “Let’s crack down on crime.” There are evil images

without any reflection or thought. Your books show an erotic side of evil.

DC:

They acknowledge it. I try to show stuff. Allow it to be erotic, real scary.

Allow it to be moving, all these different things, so it’s not just presented

as titillating or disgusting because that’s the way it’s usually presented.

It’s usually presented in a Friday The 13th kind of way, and that’s fine, but

that’s a very superficial way to present violence. It just makes it sexy. And

the other way is to make it disgusting, so you can’t even look at it. So the

idea of me, the way that I’m different, is that I actually present it so that

it’s visible. Make the actual act of evil visible, and give it a bunch of

facets so that you can actually look at it and experience it. You’re seduced

with dealing with it. You have to decide what you actually think. So with

Frisk, at the end of the book, when you find out that it’s not real, it’s like you

decide. Whatever pleasure you got out of making a picture in your mind

based on that letter of those people being murdered. You take responsibility

for it. The writer is not letting you off the hook. It’s fiction. The whole

thing is a fiction. I’m interested in writing about that stuff, and in that way

maybe I’ll understand it.

The

story gives you, the reader, a sense that it’s still a book and words.

DC:

That’s the best a book can do. It’s a collaboration. That’s why horror movies

are so limited in what they can do. That’s why Salo is, for me, not a very good

film. You look at that, and think “This is silly!” These people don’t look

real. You can see that stupid makeup. When you read a book, and when you read

that letter in Frisk, the idea is that you’re creating the picture. You’re the

one that has to create the picture of what the kid looks like. What it would be

like to look inside his body or whatever. So the idea is why do you think that

way?

So

the letter in Frisk is a metaphor for the writer’s function: he provides the

materials (or the fantasies) so the reader can imagine and collaborate?

DC:

Just like “Dennis” in the book is looking for someone to help him kill someone,

the writer is looking for readers who feel the same way he does about violence.

It’s the same thing. In some ways, that book was like dangling bait to find out

like if I wasn’t insane. I really like this stuff.

You

were talking about horror films earlier. How much has film influenced your

writing style?

DC:

The editing stuff? It seems to me that filmic editing is way more interesting

than the editing in traditional novels, which is so slow. The way film edit:

chop, chop, chop. Cutback and so forth. I mean it’s a lot easier. I’m more

interested in that. And As far as horror films: I enjoy them, but in liking

them I realize how limited they are. They’re not giving you anything. It’s like

giving you candy. If you’re interested in horror, horror films give you a little

treat, but they don’t tell you anything about horror or violence. To me, they

don’t. If your imagination is in the middle, at one extreme is an autopsy

video, which shows you real violence, at the other end is Nightmare on Elm

Street.

There

was this group of writers during the 70s and 80s called “New Narrative.” Steve

Abbott and Kevin Killian among them. How do you fit in with them? How are you

different? What is the New Narrative all about?

DC:

No one ever figured it out. There was a group of people, but there was never

anything to be involved with. People started to characterize that group of

people that way. I mean, I like all those people, including Bob Gluck and Dodie

Bellamy. I like all their work. I think that it never went anywhere because no one

could figure out what it was. Steve Abbott invented the term. All the work was

independent and experimental I guess, and it’s somehow involved with

autobiography in a funny way. We all like each other’s work. Sometimes, Kathy

Acker is in the group, and sometimes she’s not. And sometimes Lynne Tillman.

It’s a real blurry category. There is this new book coming out about New

Narrative, this year. It’s an academic book, so maybe they’ll tell us what it

is.

Is

it like the Nouveau Roman?

DC:

Except that the Nouveau Roman is a little bit more specific. They at least had

a credo. I don’t think we have any credo. Nouveau Roman writers were all

interested in the objective voice. Wasn’t that their thing? I always thought

that they were like that at the beginning. They all gave up on it. All of them

sold out, or became better. I think that you’re right: they’re a little more

alike then we are. I may be wrong. Maybe it’s not for me to say.

I

read recently a letter you wrote to Kevin Killian. I guess you were writing

Closer at the time. Less than Zero by

Bret Easton Ellis had come out and you panicked. Could you talk about that?

DC:

Where did you read that? At Kevin’s house? It was published? Oh yeah! It

freaked me out. It was weird. It came out and all of my friends said “Don’t

read this book, because it will really freak you out, because he writes so much

like you” So I didn’t read it. Then I finished Closer. Then I read it, because

I was finished with my book, so I figured whatever. And I was really freaked

out about it. Now I see the difference, but at the time I thought “Oh, this kid

has done all this stuff that I’m doing, and this book is a big success, and my

work is so artsy compared to this.” I started to get weird. It really did freak

me out. It seemed serious. When I read it, I thought that this was a serious

book. There had never been a book like Less Than Zero. He did capture a certain

thing. I was certainly impressed with it. Consequently, I have no interest in

him at all.

Could

you talk about your project with director David Lynch?

DC:

That didn’t work out. Well, this guy who is David Lynch’s assistant, his right

hand man, he does a lot of work for David Lynch. His name is John Wentworth. He

was making a movie. He wanted me to write this movie with him. It was

going to be called Lethal Injection..

We started to work on it and we had totally different ideas how it should be

like. It fell apart. We may or may not do another project. I wasn’t interested

in what he wanted to do. The non-collaboration lasted six months. Now, David

Lynch is willing to give us the money. He’s willing to put up three million

dollars for a project, if we can come up with a project. Our ideas are so

different about what we want to do. I’m not a filmmaker. So I said to John

“Maybe you should just do it yourself.” The screenplay was going to be based on

a novel called Lethal Injection,

which is a Black Lizard book. It’s a dumb book, but we were going to fix it.

It’s about a guy who gives lethal injections to prisoners on death row. Then,

he kills this guy. He becomes really interested in this guy he’s killed, and

then he becomes involved with the dead guy’s girlfriend. He becomes a junkie.

All this stuff. It’s that kind of story.

Your

book Frisk is also being made into a movie. How is that going?

DC:

They’re shooting it right now. How it started was three years ago, at the party

for Frisk, this guy, Marcus, came up to me and said “I want to do a movie of

this.” I said OK. He optioned it for three years now. They had a few directors

lined up to do it. including James Hebert, who’s done a lot of REM videos. Now

this guy, Todd Vereau is going to direct it. He’s only done a couple of short

films. He wrote the script for Frisk. The music is being done by Bob Mould.

That’s the part that I like the best. And Lee Renaldo of Sonic Youth is doing

some music for it. They’re shooting it right now. Steve Buscemi and Craig

Chester are in it. Maybe I’ll make a cameo. It’s not much like the book. I have

mixed feelings about it.

Let’s

talk about the new book TRY. Do you feel with this that you’re doing something

different stylistically from the other novels or is it all the same?

DC:

No. The only thing that’s the same about my books is that I’m interested in the

same kinds of people, but the books are really different I think. This book is

more about emotion and less about the body. Originally, I wanted to write a

book about Ziggy because I had known this kid. He was this really fucked up

kid. Really great, brilliant, weird kid. He was adopted by two gay men. While I

was working on it, my best friend got addicted to heroin, and it was a big

mess. So I spent a year of my life trying to help him get off heroin. That got

involved in it. I wanted to write about that. He and I became really close

friends. It became a really deep and strong relationship. I wanted to write

about that relationship, because it was the first time in my life that I really

felt that I loved somebody a lot. It wasn’t sexual or romantic. It was really

not. I wanted to bring that into the work, because I was really feeling that

and worried about it. So it came out of this weird emotional turmoil. The other

characters are there to present threat. It’s different to me because it’s

really about emotion. In the same way I used to talk about the body, this time

it’s about how all these people with emotions exploding out all the time. It’s

about how the emotions interlock with each other, and the way the writings, the

different sections interlock, and the characters interlock with each other.

Since

you've turned 40, you must have stopped doing drugs and drinking alcohol?

DC:

I'm not even drinking now. I'm eating better. I'm healthy. I was a mess for a

while. I like drugs a lot. I like crystal meth and acid. I like mushrooms. I

like all drugs except heroin. I'm trying to be productive. I just went through

a binge, a year ago. I'm 41 and it takes its toll. You just can't do it anymore.

Your

work seems to be the most complex explanation of how pornography influences the

mind of a male and his sexuality. How did you become so interested in porno?

DC:

That’s just the way it is. I started reading porno when I was really young. And

like a lot of people, I read a lot of porno before I had sex. By the time I was

having sex, I expected it to be like porno. When it wasn’t, I invented porno to

go with my sex, because while you’re doing your limited little things with your

body, there’s all this stuff going on in your head about what you could be

happening. I think porno is interesting. I like the way it’s structured. I’ve

studied it through my writing. I like how fake it is. You can study it for how

they really think about each other. It’s like a science book. Sex is the best

moment in life, right? If it’s really good. I like porno. I buy porno all the

time. It doesn’t matter to me what is actually happening in sex. I like the

types. I look for types of people that interest me.

Who’s

your favorite porn star?

DC:

Who’s my favorite porn star of all time? Pierre Buisson is my favorite. He’s in

Cutting Nose films.

Does

anyone come up to you with some strange porno or stuff films, and forces you to

watch?

DC:

Usually it's the other way around. But I don't have it nor know where to get

it. People want me to tell them. That's it. Everybody wants it, but no one has

it. So everyone comes to me figuring I know where it is.

How

do you feel about the idea of porno being cerebral?

DC:

I think that using porno is cerebral. Yeah. Sure. Apart from the components of

the parts of the people that are involved in it, you can do whatever you want

with it. It's all about filling in a blank. Animating these bodies that are

frozen or if it's video, I don't know what you do. You're always filling in

these people with whatever content you want to make them more desirable. I

don't know about it being cerebral.

But the use of it is. It's like a study. It's like a text.

During

this tour you read from a section from

the middle of Try about Ziggy interviewing the heavy metal kid. You said that

this is the only section that I can read from. I wanted to ask you what was the

reason for that?

DC:

Because I found that it's really impossible for me to read it. Most of Try is

fast changes from person to person, and I can't do it. I've tried it. It

doesn't work. I can't do the voices. The section that I've been reading is the

only long section written in one voice and one scene. That's why. This book has

more dialogue in it. I wanted to see what it was like to work with dialogue.

Now, not at all. It's more difficult for me to read aloud than the other

novels. I have a hard time reading dialogue. It doesn't sound like it because I

worked so hard on reading that section. It's not something that I feel

comfortable doing. I think it's sort of silly. These are just configurations in

the prose, they're not people. When you read it aloud, you have to make them

people and put emotion in their voices. I always feel that's kind of false. It's

fake. You have to do that to make it work, to get people involved in it. I feel

like a showman, and I don't like that so much.

What

kind of books do you like generally?

DC:

I don't like literature that's like mine. I hate Paul Russell. John Rechy

compared me to Russell. Rechy lives down the street from me. Yeah. He's a

prick. He's an idiot.

I

think that S&M is more visible in the culture. Do you have any interest in

that practice?

DC: No. No interest at all. It's not my thing at all. I have total respect for it, but I'm interested in insanity. I think violence is an act of insanity and chaos. When it's ritualized, it's fun but it doesn't particularly interest me.

DC: No. No interest at all. It's not my thing at all. I have total respect for it, but I'm interested in insanity. I think violence is an act of insanity and chaos. When it's ritualized, it's fun but it doesn't particularly interest me.

Many

of your books have the situation of older men and younger kids. That whole

concept is still rejected by society. What do you think about it?

DC:

That's a real complicated one. I have real mixed feelings about it. I don't

know what I think about it. I think that people should do whatever they want to

do, and it's totally plausible to me that a 10 year old could have a fulfilling

relationship with a 40 year old, but I'm also really suspicious of adults

exploiting young people. So I'm really torn about it. I don't think that they

should stop MANBLA or anything. There are plenty of examples of relationships

that have been fine. All my friends had sex when they were young with older

men, and it's fine. I'm suspicious of the power imbalance. It's really scary to

me. It makes me nervous, but I don't think that they should regulate it or

anything. In my books, it's not presented as the most positive thing in the

world. I have friends who are pedophiles, and it's fine.

It

seems like many serious writers are now writing for magazines like Esquire,

Harper's, and Spin. How have your experiences been with doing journalism and

working for magazines?

DC:

You don't make much money from writing. I don't like doing journalism at all. I

did an interview with Keanu Reeves. That was fun. Interview magazine is the

best, but I haven't done anything with them since. They give you all this

money. You get to interview a star. They transcribe the tapes. It's amazing. I

need to do something to make money, and I don't mind doing it. It's not

something that I really wanted to do. It was fun hanging out with Courtney

Love. I liked it. Spin magazine flew me out to Seattle, and I interviewed the

band. I hung out with her, then Î went over to Courtney's house. I played with

Francis Bean. I talked with them till 5:30 in the morning. All this shit, while

they did a photo shoot. It took a couple of days. I wish that I could make more

money with my books. I wouldn't do journalism. I don't think that I'm very good

at it, but I think I'm getting a little better. There are people who are real

good journalists. As a journalist, I wish that I could write like the early

Hunter Thompson or the early Tom Wolfe. Their journalism is real good. The

Gonzo journalism is real great. Maybe the best thing about being a journalist

is that you get free stuff.

No comments:

Post a Comment